Computer programs are traditionally organized as one-directional computations, which perform operations on prespecified arguments to produce desired outputs. On the other hand, we often model systems in terms of relations among quantities. For example, a mathematical model of a mechanical structure might include the information that the deflection d of a metal rod is related to the force F on the rod, the length L of the rod, the cross-sectional area A, and the elastic modulus E via the equation dAE = FL. Such an equation is not one-directional. Given any four of the quantities, we can use it to compute the fifth. Yet translating the equation into a traditional computer language would force us to choose one of the quantities to be computed in terms of the other four. Thus, a procedure for computing the area A could not be used to compute the deflection d, even though the computations of A and d arise from the same equation.

In this section, author sketchs the design of a language that enables us to work in terms of relations themselves. The primitive elements of the language are primitive constraints, which state that certain relations hold between quantities. For example, (adder a b c) specifies that the quantities a, b, and c must be related by the equation a + b = c, (multiplier x y z) expresses the constraint xy = z, and (constant 3.14 x) says that the value of x must be 3.14.

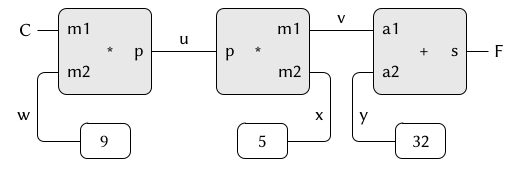

This language provides a means of combining primitive constraints in order to express more complex relations. We combine constraints by constructing constraint networks, in which constraints are joined by connectors. A connector is an object that “holds” a value that may participate in one or more constraints. For example, we know that the relationship between Fahrenheit and Celsius temperatures is 9C = 5(F − 32). Such a constraint can be thought of as a network consisting of primitive adder, multiplier, and constant constraints.

In the figure, we see on the left a multiplier box with three terminals, labeled m1, m2, and p. These connect the multiplier to the rest of the network as follows: the m1 terminal is linked to a connector C, which will hold the Celsius temperature. The m2 terminal is linked to a connector w, which is also linked to a constant box that holds 9. The p terminal, which the multiplier box constrains to be the product of m1 and m2, is linked to the p terminal of another multiplier box, whose m2 is connected to a constant 5 and whose m1 is connected to one of the terms in a sum.

Computation by such a network proceeds as follows: When a connector is given a value (by the user or by a constraint box to which it is linked), it awakens all of its associated constraints (except for the constraint that just awakened it) to inform them that it has a value. Each awakened constraint box then polls its connectors to see if there is enough information to determine a value for a connector. If so, the box sets that connector, which then awakens all of its associated constraints, and so on. For instance, in conversion between Celsius and Fahrenheit, w, x, and y are immediately set by the constant boxes to 9, 5, and 32, respectively. The connectors awaken the multipliers and the adder, which determine that there is not enough information to proceed. If the user (or some other part of the network) sets C to a value (say 25), the leftmost multiplier will be awakened, and it will set u to 25 · 9 = 225. Then u awakens the second multiplier, which sets v to 45, and v awakens the adder, which sets f to 77.

What’s about code?

As you may have noticed this program is very similar to the previous one, but without delay simulating. All code is here.

Excecuting part contains connectors, celsius-fahrenheit-converter, a couple of testers and code, which changes input values.

(def C (make-connector))

(def F (make-connector))

(celsius-fahrenheit-converter C F)

(probe "Celsius temp" C)

(probe "Fahrenheit temp" F)

(set-value! C 25 'user)

(println "-----------------------------------")

(set-value! F 212 'user)

(println "-----------------------------------")

(forget-value! C 'user)

(println "-----------------------------------")

(set-value! F 212 'user)

(println "-----------------------------------")

;; output:

;; set value C = 25

;; Probe: Celsius temp = 25

;; Probe: Fahrenheit temp = 77

;; -----------------------------------

;; set value F = 212 and don't forget C

;; Contradiction ( 212 , 77 )

;; -----------------------------------

;; forget C

;; Probe: Celsius temp = ?

;; Probe: Fahrenheit temp = ?

;; -----------------------------------

;; set value F = 212

;; Probe: Fahrenheit temp = 212

;; Probe: Celsius temp = 100

;; -----------------------------------